#11 Bit by Bit: Reframing Sharks

What do we really know about these creatures, besides »Jaws«? Marine biologists and their most recent research/writing can tell.

[This newsletter will be published in English for the time being as there seems to be a broader audience to reach on Substack.]

Sharks are monsters – at least that’s what generations of teenagers have been led to believe watching Jaws. The iconic movie celebrates its 50th anniversary these days. What did it convey? Just as people look forward to a carefree summer by the sea, it introduces an unexpected fear: the haunting possibility of being fatally wounded and dragged into the depths by one of those Great White sharks. Monsters.1

The monstrous Great White of Jaws turned into a meme – and this meme became the dominant image of these animals’ species. Wrongly so.

Usually, there are about 100 human-shark incidents globally recorded each year, 10 per cent of them fatal. But a recent study only proves: Sharks don’t kill – they make a living. Behavioural ecologist Eric E. G. Clua and his team analyzed existing data from 1942 to 2023 from French Polynesia, where human-shark encounters are quite frequent. They came to surprising conclusions, introducing the concept of self-defense in sharks.

Defensive bites when handling sharks by hand

This self-defense is particularly associated to human activities – like underwater spearfishing, managing traditional fish traps, or even handling the sharks with bare hands (for photography or as tourist attractions): »Following an initial agonistic behavior by a human on a shark,« Clua et al. write, »a pattern of self-defense bites ensues, characterized by immediate aggression in return.« These kinds of defensive bites usually come »with minimal tearing of flesh« and are rarely fatal – whereas a predation motivation on humans typically »involves heavy loss of tissue«, the study says.

Sharks’ self-defense is quite rare: 16 out of 137 shark bites documented in French Polynesia fall into this category. However, the scientists identify several other categories of the sharks’ motivation to attack (with/without feeding trigger), like »reflex/clumsiness«, »dominance-territoriality«, or »antipredation or fear motivation, when a shark anticipates a potential human aggression before it occurs«. Such an attack might be triggered by reducing the sharks range to escape, for example, by »a scuba diver approaching a shark quickly with an underwater scooter«, one of the examples featured in the study states.

Therefore, the scientists recommend untrained persons never to attempt to rescue a distressed shark. It’s only reasonable to raise this caution sign, given increased incidents between humans and large carnivors in terrestrial and marine settings. Also, today’s »more sustainable wildlife management approach requires a better understanding of what motivates animals to attack people«, they write. In the best case, studies like this one lead to less (endangered) animals being killed in their species-specific living environment in defense of human activities.

»Eerily familiar creatures«

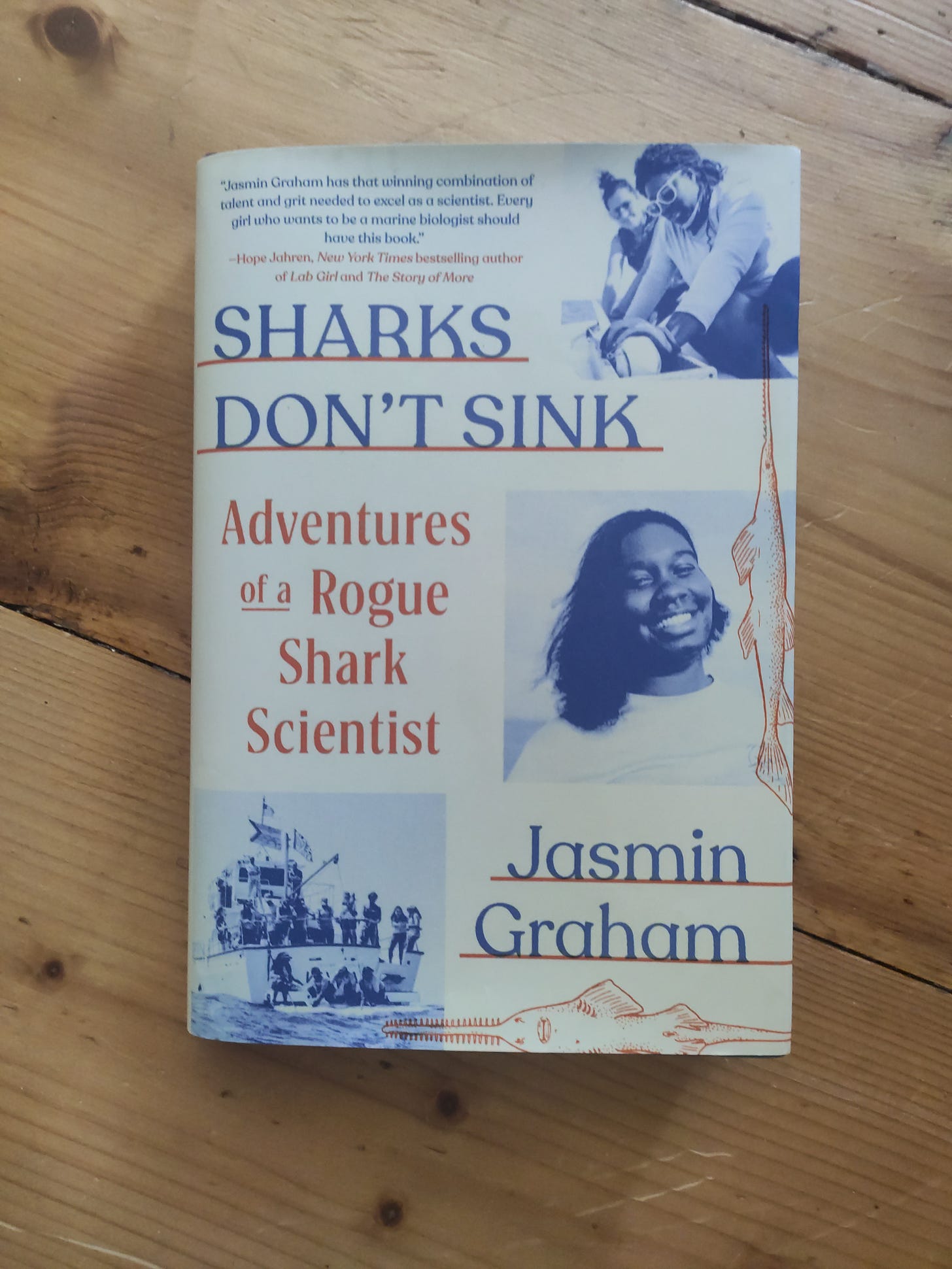

»The negative stereotypes and fearmongering surrounding these creatures«, Jasmin Graham writes about sharks, »felt eerily familiar to me as someone who’s grown up Black in a country where we’re assumed to be threatening, even when we’re just minding our own business.« Graham, marine biologist and author of Sharks Don’t Sink (2024)2, reflects on her own role as a »rogue scientist« and sometimes being the only Person of Colour in scientific environments. In her book, she inspiringly intertwins the story of researching sharks with her own coming-of-age – she »fell in love with the water as a child, fishing with my dad«.

So, not only are sharks no monsters. They, furthermore, are able to teach us a lesson: »Weirdos like hammerheads can teach us a lot, because they offer us so many questions«, Graham writes. Most of sharks’ species look basically like one another, »and then you have these other ones [the hammerheads] with wild, bizarre heads. What’s going on there? What does this head do?« Also evolutionarily: »If it has been passed down again and again, it must be important, right? So what invaluable role does it play?« We don’t know yet.

Hammerheads alienate humans: They confuse us. And therefore, they represent the ultimate argument to keep on doing research. And keeping these subjects of research alive. Clua et al. mention in their study, that only 2023 a comprehensive shark ethogram was published. An ethogram is a kind of behavioural catalogue, documenting and categorizing the typical behaviour of one (or several related) species, describing their way to show courtship, sociality, aggression etc. »We suggest that the media, which often sensationalizes (…) self-defense bites as attacks, could help to improve attitudes toward sharks and their conservation by more objectively reporting the culpability of humans in triggering them«, Clua and his team write, giving us a clue to help in this endeavour.

Whether you’ll spend it by the sea, in the mountains, at a lake or at home: try to look forward to a summer as carefree as possible! Yours, Patricia

In some cases, though, the movie »fueled a [scientific] passion«, the New York Times reports.

Graham, Jasmin (with Makeba Rasin; 2024): Sharks Don’t Sink. Adventures of a Rogue Shark Scientist, Pantheon Books: New York.